Libor Rising to the Occasion

What You Will Find Here

- OJOS11

- Articles and news of general interest about investing, saving, personal finance, retirement, insurance, saving on taxes, college funding, financial literacy, estate planning, consumer education, long term care, financial services, help for seniors and business owners.

READING LIST

Blog List

-

-

Charlie Javice takes 'full responsibility,' asks for mercy ahead of JPMorgan Chase fraud sentencing - "There are no excuses, only regret," Javice wrote her judge Friday night, ahead of her sentencing for defrauding JPMorgan Chase out of $175 million

-

Energy Secretary Expects Fusion to Power the World in 8-15 Years - From theory and small-scale tests to reality, will fusion ever scale?

-

The Billion-Dollar Stakes for OpenAI - The artificial intelligence giant is closing in on a deal with Microsoft regarding its future governance, but other questions stand over its huge costs.

-

Everybody Else Is Reading This - Snowflakes That Stay On My Nose And Eyelashes Above The Law Trump’s New Birth Control […]

-

Maximizing Employer Stock Options - Oct 29 – On this edition of Lifetime Income, Paul Horn and Chris Preitauer discuss the benefits of employee stock options and how to best benefit from th...

-

Wayfair Needs to Prove This Isn't as Good as It Gets - Earnings were encouraging, but questions remain about the online retailer's long-term viability.

-

Hannity Promises To Expose CNN & NBC News In "EpicFail" - *"Tick tock."* In a mysterious tweet yesterday evening to his *3.19 million followers,* Fox News' Sean Hannity offered a preview of what is to come from ...

-

Don’t Forget These Important Retirement Deadlines - *Now that fall is in full swing, be sure to mark your calendar for steps that can help boost your tax-advantage retirement savings.*

Showing posts with label fixed income. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fixed income. Show all posts

How to Invest in a Rising Rate Environment (Morningstar)

Preferred Stocks Frequently Asked Questions (from Incapital.com)

Preferred Security FAQs

- How do I purchase preferred securities?

- What are cumulative and non-cumulative dividends?

- Are preferred securities callable?

- Is the income from preferred securities taxable?

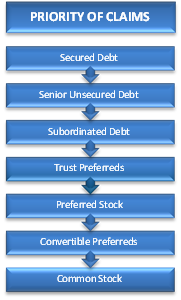

- Where do preferred securities stand in the priority of claims?

- Where can I get a prospectus or prospectus supplement?

HOW DO I PURCHASE PREFERRED SECURITIES?

After syndication, most public preferred securities are traded on an exchange. The most widely used is the New York Stock Exchange. They also trade over-the-counter through broker-dealers who make markets in various preferreds. Privately-placed preferreds trade through a broker-dealer or directly between investors.

WHAT ARE CUMULATIVE AND NON-CUMULATIVE DIVIDENDS?

Preferred stock dividends are either cumulative or non-cumulative. Cumulative dividends are due to shareholders irrespective of an issuer’s profitability. If an issuer has trouble meeting its financial obligations and does not pay a cumulative dividend, dividends accrue and the company is obligated to pay all past and currently due preferred dividends before paying common dividends. If a company does not pay a non-cumulative dividend, it is not obligated to do so in the future. Non-cumulative dividends do not accrue beyond one year and the issuer is still permitted to pay common dividends the year following an omission if preferred payments recommence. In either case, a company is not automatically considered in default if it misses a payment as it would be by missing a bond payment.

ARE PREFERRED SECURITIES CALLABLE?

Preferred securities may be callable, in which case the issuer has the right to purchase the securities from the investor at a predetermined date and price.

IS THE INCOME FROM PREFERRED SECURITIES TAXABLE?

Income from preferreds with the exception of Trust Preferreds is taxable as ordinary income unless it is Qualified Dividend Income (QDI) and/or Dividend Received Deduction (DRD) eligible. QDI and DRD eligibility depends on factors relating to the structure, issuer and investor.

Income from Trust Preferreds and Baby Bonds is considered interest and taxable as ordinary income.

The tax treatment of preferred securities varies. However, investors should not rely on these taxation provisions, as they may change. Incapital does not provide tax or financial advice. Please read the tax section of the prospectus and prospectus supplement and consult a qualified tax professional before investing.

WHERE DO PREFERRED SECURITIES STAND IN THE PRIORITY OF CLAIMS?

The priority of claims refers to the order in which investors receive their share of a firm’s net worth upon liquidation. Preferred securities rank junior to bonds and senior to common stock in the priority of claims against a company’s assets in the event of bankruptcy or reorganization. The diagram below illustrates the capital structure priority. A preferred’s place may vary depending on its specific characteristics outlined in the prospectus and prospectus supplement.

This Priority of Claims diagram is for illustrative purposes only. Each security’s offering documents will govern the issue’s priority.

WHERE CAN I GET A PROSPECTUS OR PROSPECTUS SUPPLEMENT?

The prospectus and prospectus supplement for public offerings are available on the SEC’s website.

High Yielding Hybrid Securities (Alliance Bernstein)

Bank Hybrids Bloom Globally—with Subtle Variations

The market for financial hybrid securities is growing as banks worldwide implement stringent new capital rules. But not all hybrids are alike, so investors can’t afford to take a one-size-fits-all approach.

These securities do have important common features. Because they were created to comply with the Basel III global banking regulations that aim to improve banks’ ability to withstand financial stress, all of them can be written down or converted to equity if the issuing bank runs into trouble. This process ensures that shareholders and creditors will bear the cost of any future bank rescue, not taxpayers.

Banks around the world have already issued more than $200 billion of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) securities, which would be the first bonds to absorb losses in a crisis, and we expect issuance to nearly double in the years ahead (Display 1).

Even so, these securities have important structural differences that can affect performance, and pinpointing the most attractive opportunities requires disciplined analysis and global expertise.

It’s the Economy—and the Credit Cycle

The first thing managers need to navigate this growing market is a deep understanding of regional economic conditions and credit cycles around the world. For example, banks in the US and Europe are several years into the process of building up capital and reducing risk, leaving their banking sectors stronger and healthier than they were before the financial crisis.

At the same time, the economic backdrop has brightened considerably in the US and the UK, while the euro area appears to be in the early stages of a recovery. As we pointed out in earlier posts, this combination of stricter regulations and improved fundamentals makes US preferred securities and European AT1 debt attractive.

With stronger balance sheets, US and European banks are less likely to run into the kind of trouble they did in 2008. That strength helps offset the risk of losses on these assets and means investors can pocket the high yields they offer in exchange for their lower perch in the capital structure. So far this year, yields on these assets have been above those available from BB-rated US high-yield debt (Display 2).

Things look different in other parts of the world. Managers might want to take a more cautious approach in countries more sensitive to commodity prices or in those that have recently undergone credit booms and rapid home price increases. A slowdown in economic growth in these instances could lead to a spike in bad loans and trigger increased volatility in banks’ outstanding hybrid securities.

Of course, it’s also important for managers to do their homework when it comes to individual banks, no matter what their country of origin, which means having a strong handle on a bank’s fundamental health and credit metrics. Put another way, managers should be comfortable investing in a bank on a stand-alone basis.

Regulatory Regimes: Read the Fine Print

Variations in local regulatory regimes matter, too. For instance, in the US, any form of exceptional government support for banks—think the 2008 bailouts—would trigger the mandatory write-down or conversion-to-equity provisions on US preferred securities.

That’s not so in Japan, where the rules were written to give the government the flexibility to support banks in certain circumstances, without automatically triggering write-downs and exposing investors to losses. Astute managers need to understand these subtle differences.

Understanding Structural Nuances

At a more micro level, managers will need a deep understanding of the structural features of individual securities. Again, while the structure is broadly similar across securities and regions, there are subtle differences. These differences can sometimes cause the market to mis-price securities, providing astute investors with opportunities to boost relative value in their portfolios.

An AT1 security from a European bank priced in US dollars might, for instance, trade differently than one priced in euros. Investors also need to be aware of the varying supply-and-demand factors in different markets, which can affect how these securities are priced.

Raising the Regulatory Bar

As with any investment, there are risks associated with these Basel III–compliant securities. For some investors, the possibility of being wiped out in a crisis may be too big a risk to bear. But as we’ve noted, the level of risk in this sector varies, depending on the individual security, the issuing bank, and the regional economic and regulatory environment.

What’s more, global regulators have shown no sign of easing up on banks. Regulations are becoming more stringent and are being applied more widely. As a result, many banks will continue to reduce leverage and hold more capital as a cushion against losses—things that should be music to any bondholder’s ear.

We think those factors make hybrid securities a promising way to potentially boost returns in a low-yield environment. But global know-how and thorough analysis are critical for making the most of this growing opportunity.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams

Combat Inflation with Floating Rate Securities (Forbes)

Fixed-Income Watch

Inflation Protection For Free

Richard Lehmann, 09.12.11, 6:00 PM ET

I have been pounding the table warning about rising interest rates for some time now. Well, it hasn't happened yet, and the latest Fed pronouncement makes it clear that short- and long-term rates will likely stay low for the next two years. My fear of rising rates caused me to recommend adjustable-rate securities. I was wrong on inflation, but my floating-rate picks have done quite well.

Since 2009 the adjustable-rate securities have enjoyed a spectacular resurgence, because most of them were issued by banks and other financial institutions that suffered huge declines during the financial crisis. These "too big to fail" institutions needed capital, and they issued all kinds of paper to bolster their books.

While fixed-rate issues experienced a similar rise, they are hurt by their call provisions. Specifically, most of the issues with a 5% or higher coupon rate are likely to be refinanced. This means they're trading on a yield-to-call basis with measly returns measured in basis points rather than percentages (100 basis points equals one percentage point). Most are trading above the par value at which they will be redeemed. Those who bought fixed-rate capital note preferreds with high coupons, issued by the troubled banks in 2008, thought they would be safe from call until 2013. Not so.

Congress and the Dodd-Frank Act foiled this seemingly smart strategy. That act says these preferreds can no longer be considered part of a bank's tier-one capital. This triggers a "statutory change" loophole that now allows banks to call these fixed-rate preferreds early. Think of it as Chris Dodd's going away present to his banker buddies.

Adjustable-rate securities normally trade at lower yields than comparable fixed-rate securities. They pay interest monthly or quarterly based on a Treasury bond index, LIBOR or changes in the CPI. The floating rate means these notes are designed to trade at par. But this hasn't been happening. That is because these securities come with an interest rate floor, typically at about 4%. When these bonds were issued that was considered meager. Today a 4% yield is a king's ransom.

Despite the healthy yield floor, most of these adjustables are selling below par today because they are viewed as inflation hedges in a period when inflation fears are absent. Thus you can still buy these adjustable-rate securities below par value. That is like getting a dollar for 90 cents. Hence, inflation protection is free, and the call risk is a positive. Once inflation fears are rekindled and rates spike, you'll be all set with these floating-rate securities.

Here are some adjustables you should consider buying:

AEGON NV SERIES 1 (AEB, 17) PERPETUAL PREFERRED RATED BAA2/BBB/BBB. This Dutch multi-line insurance giant was hard-hit during the financial crisis and still suffers under the weight of European banking concerns. This preferred is adjustable quarterly based on three-month LIBOR plus 87.5 basis points. It has a 4% floor and no ceiling, so at its current price it yields 5.71%. Even better, it's eligible for the 15% qualified dividend income tax rate for those in the highest tax bracket.

Closer to home I like GOLDMAN SACHS SERIES A PERPETUAL PREFERRED (GS A, 19) RATED BAA2/BBB–/A–. It has a floor rate of 3.75% and no ceiling and is tied to three-month LIBOR plus 75 basis points. It yields 4.93%, and it also benefits from the preferable tax rate on dividend income.

If you are willing to accept more risk buy the SLM CORP. 0% OF 3/15/17 (OSM, 21) RATED BA1/BBB–, yielding 6.15%. SLM is better known as Sallie Mae, the student loan organization, which went private in 2004. This adjustable is different in that it pays monthly, based on the percentage change in the year-over-year Consumer Price Index, plus 200 basis points. It has no floor or ceiling rate and currently pays 5.164%. I like it because there is no delay in recognizing an uptick in inflation, but unfortunately it isn't eligible for lower tax treatment.

I thought rates would climb because the Fed would use inflation as its primary tool in curing our economic woes. Bernanke flooded our economy with dollars, but inflation failed to materialize. Our economy was much weaker than I thought. Dark clouds still hang over global markets. While inflation is not an immediate concern, it can and does crop up when it's least expected. Given the current international turmoil and clearly nervous markets, investments offering inflation protection at no cost are a gift I find hard to resist.

Inflation Protection For Free

Richard Lehmann, 09.12.11, 6:00 PM ET

I have been pounding the table warning about rising interest rates for some time now. Well, it hasn't happened yet, and the latest Fed pronouncement makes it clear that short- and long-term rates will likely stay low for the next two years. My fear of rising rates caused me to recommend adjustable-rate securities. I was wrong on inflation, but my floating-rate picks have done quite well.

Since 2009 the adjustable-rate securities have enjoyed a spectacular resurgence, because most of them were issued by banks and other financial institutions that suffered huge declines during the financial crisis. These "too big to fail" institutions needed capital, and they issued all kinds of paper to bolster their books.

While fixed-rate issues experienced a similar rise, they are hurt by their call provisions. Specifically, most of the issues with a 5% or higher coupon rate are likely to be refinanced. This means they're trading on a yield-to-call basis with measly returns measured in basis points rather than percentages (100 basis points equals one percentage point). Most are trading above the par value at which they will be redeemed. Those who bought fixed-rate capital note preferreds with high coupons, issued by the troubled banks in 2008, thought they would be safe from call until 2013. Not so.

Congress and the Dodd-Frank Act foiled this seemingly smart strategy. That act says these preferreds can no longer be considered part of a bank's tier-one capital. This triggers a "statutory change" loophole that now allows banks to call these fixed-rate preferreds early. Think of it as Chris Dodd's going away present to his banker buddies.

Adjustable-rate securities normally trade at lower yields than comparable fixed-rate securities. They pay interest monthly or quarterly based on a Treasury bond index, LIBOR or changes in the CPI. The floating rate means these notes are designed to trade at par. But this hasn't been happening. That is because these securities come with an interest rate floor, typically at about 4%. When these bonds were issued that was considered meager. Today a 4% yield is a king's ransom.

Despite the healthy yield floor, most of these adjustables are selling below par today because they are viewed as inflation hedges in a period when inflation fears are absent. Thus you can still buy these adjustable-rate securities below par value. That is like getting a dollar for 90 cents. Hence, inflation protection is free, and the call risk is a positive. Once inflation fears are rekindled and rates spike, you'll be all set with these floating-rate securities.

Here are some adjustables you should consider buying:

AEGON NV SERIES 1 (AEB, 17) PERPETUAL PREFERRED RATED BAA2/BBB/BBB. This Dutch multi-line insurance giant was hard-hit during the financial crisis and still suffers under the weight of European banking concerns. This preferred is adjustable quarterly based on three-month LIBOR plus 87.5 basis points. It has a 4% floor and no ceiling, so at its current price it yields 5.71%. Even better, it's eligible for the 15% qualified dividend income tax rate for those in the highest tax bracket.

Closer to home I like GOLDMAN SACHS SERIES A PERPETUAL PREFERRED (GS A, 19) RATED BAA2/BBB–/A–. It has a floor rate of 3.75% and no ceiling and is tied to three-month LIBOR plus 75 basis points. It yields 4.93%, and it also benefits from the preferable tax rate on dividend income.

If you are willing to accept more risk buy the SLM CORP. 0% OF 3/15/17 (OSM, 21) RATED BA1/BBB–, yielding 6.15%. SLM is better known as Sallie Mae, the student loan organization, which went private in 2004. This adjustable is different in that it pays monthly, based on the percentage change in the year-over-year Consumer Price Index, plus 200 basis points. It has no floor or ceiling rate and currently pays 5.164%. I like it because there is no delay in recognizing an uptick in inflation, but unfortunately it isn't eligible for lower tax treatment.

I thought rates would climb because the Fed would use inflation as its primary tool in curing our economic woes. Bernanke flooded our economy with dollars, but inflation failed to materialize. Our economy was much weaker than I thought. Dark clouds still hang over global markets. While inflation is not an immediate concern, it can and does crop up when it's least expected. Given the current international turmoil and clearly nervous markets, investments offering inflation protection at no cost are a gift I find hard to resist.

Why You Should Wait: Fixed Annuity Rates are Still Too Low (Morningstar)

The Error-Proof Portfolio:

For Annuities, Timing Is Key

By Christine Benz | 04-12-10

Many investors' hackles go up when you say the word "annuity." They immediately think of variable annuities, many of which are pricey and often sold, not bought. (When the TV program Dateline is using hidden cameras to catch salespeople in the act of peddling inappropriate products to unwitting seniors, it's fair to say that an industry has an image problem.)

But plain-vanilla single-premium immediate annuities deserve more respect. The concept is as simple as it can be: You give the insurance company a slice of your retirement portfolio, and the insurer, in turn, sends you back a stream of income for the rest of your life. You can layer on additional bells and whistles--such as survivor benefits in case you die early in the life of the contract--but they will dramatically decrease the payout you'll receive.

The Value Proposition

The idea of using annuities as a slice of retiree portfolios has been gaining traction in the financial-planning community and among mainstream investors during the last few years. Against the backdrop of a rocky stock market and a shrinking number of defined-benefit plans, annuities' promise of a certain payout holds a lot of appeal. And with bond yields still exceptionally low right now, annuities are also attractive in that they generally deliver a higher payout than what a retiree would receive via a traditional high-quality fixed-income investment.

Annuities also help address the more basic problem that--regardless of the market environment--we're all planning for an unknowable time horizon. None of us knows how long we'll live. And increasing life spans increase the risk that a portfolio of stocks and bonds (that is, one without an annuity) might not last throughout a retiree's lifetime, thereby burnishing annuities' appeal.

Problematic Timing

For all of these reasons, it's become conventional wisdom that SPIAs should be part of retirees' toolkits. Unfortunately, fixed annuities are catching on at what could, in hindsight, be the worst possible time. That's because the payout you receive from an annuity is based on two key factors: 1) the expected life spans of other annuityholders and the likelihood that some of them will die before actuarial tables would suggest; and 2) the interest rate that the insurance company can expect to earn on your money.

The first factor--in essence, the fact that some unlucky people in the annuity pool will die before their time--is why annuities can provide a higher payout than fixed-rate investments. In a pool of hundreds of people, the statisticians know that at least some of the folks who should live into their 80s and 90s will expire in their 60s and 70s instead. Those early decedents will have paid more into the annuity than they've gotten out. Other annuitants, meanwhile, will live well beyond what the actuarial tables would suggest, enabling them to receive more than they've put into their retirement.

The wrinkle is that people are living longer, and insurance companies are having to spread the money in the annuity pool over more and more very long lives, so increasing longevity will have the side effect of shrinking the payouts for everyone. (As a side note, an interesting body of research indicates that annuity pools include significant adverse selection--that is, the people who are most likely to buy an annuity are also likely to live much longer than actuarial tables would suggest. That may be because those most attracted to annuities may have longevity in their families, or perhaps there's a correlation with wealth and better health care.)

That trend will provide a long-term headwind for annuities, but it shouldn't have a significant impact on the timing of when you buy an annuity. The other component of annuity payouts--the interest rate the insurance company can expect to earn on your money--is more problematic. If you buy an annuity today, the currently ultra-low interest-rate environment will depress the payout you receive. (It's not a perfect analogy, but it's somewhat akin to buying a long-term bond with a very low coupon. Rates may go up in the future, but you'll be stuck with your low payout.) The average fixed annuity rate plunged from 5.55% to 3.94% between December 2008 and December 2009, according to National Underwriter.

What to Do?

For those who like the concept of an annuity but are concerned about the effect of low interest rates on payouts, one possibility is to ladder your investments, essentially dollar-cost averaging in to mitigate the risk of buying an annuity when interest rates are at a secular low. If, for example, you were planning to put $100,000 into an annuity overall, you could invest $20,000 into five annuities during the next five years. Such a program, while not particularly simple or streamlined, would also have a beneficial side effect in that it would give you the opportunity to diversify your investments across different insurance companies, thereby offsetting the risk that an insurance company would have difficulty meeting its obligations.

Alternatively, a prospective annuity purchaser could simply wait until fixed-income interest rates head back up toward historical norms. While fixed-income yields have recently begun to climb, they're still extremely low relative to historic norms.

For Annuities, Timing Is Key

By Christine Benz | 04-12-10

Many investors' hackles go up when you say the word "annuity." They immediately think of variable annuities, many of which are pricey and often sold, not bought. (When the TV program Dateline is using hidden cameras to catch salespeople in the act of peddling inappropriate products to unwitting seniors, it's fair to say that an industry has an image problem.)

But plain-vanilla single-premium immediate annuities deserve more respect. The concept is as simple as it can be: You give the insurance company a slice of your retirement portfolio, and the insurer, in turn, sends you back a stream of income for the rest of your life. You can layer on additional bells and whistles--such as survivor benefits in case you die early in the life of the contract--but they will dramatically decrease the payout you'll receive.

The Value Proposition

The idea of using annuities as a slice of retiree portfolios has been gaining traction in the financial-planning community and among mainstream investors during the last few years. Against the backdrop of a rocky stock market and a shrinking number of defined-benefit plans, annuities' promise of a certain payout holds a lot of appeal. And with bond yields still exceptionally low right now, annuities are also attractive in that they generally deliver a higher payout than what a retiree would receive via a traditional high-quality fixed-income investment.

Annuities also help address the more basic problem that--regardless of the market environment--we're all planning for an unknowable time horizon. None of us knows how long we'll live. And increasing life spans increase the risk that a portfolio of stocks and bonds (that is, one without an annuity) might not last throughout a retiree's lifetime, thereby burnishing annuities' appeal.

Problematic Timing

For all of these reasons, it's become conventional wisdom that SPIAs should be part of retirees' toolkits. Unfortunately, fixed annuities are catching on at what could, in hindsight, be the worst possible time. That's because the payout you receive from an annuity is based on two key factors: 1) the expected life spans of other annuityholders and the likelihood that some of them will die before actuarial tables would suggest; and 2) the interest rate that the insurance company can expect to earn on your money.

The first factor--in essence, the fact that some unlucky people in the annuity pool will die before their time--is why annuities can provide a higher payout than fixed-rate investments. In a pool of hundreds of people, the statisticians know that at least some of the folks who should live into their 80s and 90s will expire in their 60s and 70s instead. Those early decedents will have paid more into the annuity than they've gotten out. Other annuitants, meanwhile, will live well beyond what the actuarial tables would suggest, enabling them to receive more than they've put into their retirement.

The wrinkle is that people are living longer, and insurance companies are having to spread the money in the annuity pool over more and more very long lives, so increasing longevity will have the side effect of shrinking the payouts for everyone. (As a side note, an interesting body of research indicates that annuity pools include significant adverse selection--that is, the people who are most likely to buy an annuity are also likely to live much longer than actuarial tables would suggest. That may be because those most attracted to annuities may have longevity in their families, or perhaps there's a correlation with wealth and better health care.)

That trend will provide a long-term headwind for annuities, but it shouldn't have a significant impact on the timing of when you buy an annuity. The other component of annuity payouts--the interest rate the insurance company can expect to earn on your money--is more problematic. If you buy an annuity today, the currently ultra-low interest-rate environment will depress the payout you receive. (It's not a perfect analogy, but it's somewhat akin to buying a long-term bond with a very low coupon. Rates may go up in the future, but you'll be stuck with your low payout.) The average fixed annuity rate plunged from 5.55% to 3.94% between December 2008 and December 2009, according to National Underwriter.

What to Do?

For those who like the concept of an annuity but are concerned about the effect of low interest rates on payouts, one possibility is to ladder your investments, essentially dollar-cost averaging in to mitigate the risk of buying an annuity when interest rates are at a secular low. If, for example, you were planning to put $100,000 into an annuity overall, you could invest $20,000 into five annuities during the next five years. Such a program, while not particularly simple or streamlined, would also have a beneficial side effect in that it would give you the opportunity to diversify your investments across different insurance companies, thereby offsetting the risk that an insurance company would have difficulty meeting its obligations.

Alternatively, a prospective annuity purchaser could simply wait until fixed-income interest rates head back up toward historical norms. While fixed-income yields have recently begun to climb, they're still extremely low relative to historic norms.

Best bargains in Muni Bonds Now (Barrons)

How to Play the Panic in Muni Bonds

By RANDALL W. FORSYTH

For several months, panicked investors have been pulling cash from muni-bond funds. For investors of means, that presents an opportunity to lock in high tax-free yields for a decade or more.

Since mid-November, panicked sellers have yanked about $26 billion from muni-bond funds, disrupting a usually orderly market. For investors of means, that presents an opportunity to lock in high tax-free yields for a decade or more.

Doing so, however, takes more care than buying a muni exchange-traded fund or closed-end fund.

The undeniable crisis in public finances has moved from the political background to the top of the news in recent months. The demonstrations by Wisconsin public employees protesting the governor's drastic measures to close the state's budget deficit are only the most dramatic examples of the fiscal pressures being felt all across the nation.

But the budget problems in states and localities are not nearly as dire as those of the sovereign debtors in Europe, though you might not know that from the coverage in the popular media. Most notably, analyst Meredith Whitney predicted an imminent day of reckoning for state and local governments in a December interview with CBS News' 60 Minutes. "You could see 50 sizable defaults," she asserted. "Fifty to 100 sizable defaults. More. This will amount to hundreds of billions of dollars' worth of defaults."

Last week, a consulting firm formed by "Dr. Doom," Nouriel Roubini, chimed in with a similar forecast of $100 billion of defaults, which had no discernible impact on the muni market.

Whitney's unsupported prediction of default -- vastly in excess of that seen in the Great Depression of the 1930s -- helped push muni prices down about 10% for long-term bonds. Her assertions have been met with a deluge of criticism from muni-bond professionals, as well as in the pages of Barron's and on Barrons.com. Yet many pricing anomalies persist. Investors willing to buy individual bonds and hold them to maturity can get yields as high as 5% on highly rated paper. That's equivalent to a taxable yield of nearly 7.7%.

The bonds themselves provide the assurance of repayment of principal at maturity, which provides a measure of confidence even as their prices may fluctuate. Mutual funds, whether equity or fixed-income, are worth only what they fetch that day; there is no assurance that they will recoup their losses and return the original investment.

Among the securities to look for are bonds backed by clearly defined sources of money, including thruways, water and sewer systems and state lottery revenues.

Profiting from Panic

Other factors also conspired to make for a perfect storm for municipal bonds. The Treasury market -- which determines the broad trend in other bond markets, including munis -- also has been under pressure until recently as yields rose on increasing fears over inflation and investors' preference for risk assets. In addition, the end of the Build America Bond program on Dec. 31, which provided a federal subsidy to states and localities issuing taxable bonds, added to pressures. The BABs program meant less issuance of traditional tax-exempt securities, which had bolstered their prices and kept a lid on their yields. The sunset of BABs at the end of 2010 lifted that lid. The BABs program also was important in broadening the municipal market to institutional and global investors not interested in income free from U.S. income tax, the main lure for American individual investors.

The carnage is particularly visible in the iShares S&P National AMT-Free Municipal Bond exchange-traded fund, a quick and easy proxy for the muni market. It shed more than 10% in value from its peak in August to its trough in January and still trades 6.4% below its high.

In the process, extraordinary values have emerged as yields on tax-exempt municipals rose to equal or even exceed those of taxable Treasury or corporate bonds. Taking in munis' tax advantage, high-quality tax-exempt bonds exceeded the after-tax yields on junk bonds. Around the muni market's nadir in January, tax-free yields on investment-grade California general-obligation bonds were higher than the yields on lower-quality, fully taxable bonds of Mexico or even Colombia.

While that portion of the investing public who take their investment cues from TV were stampeding out of munis, savvy and sophisticated investors were going the other way. And even as a backlash against the doomsayers for their unsupported predictions of multibillion-dollar defaults increased, they dismissed their critics as peddlers of munis merely defending their turf.

Other disinterested and distinguished observers have pointed out how undervalued munis are.

MKM Partners' chief economist and strategist, Michael Darda, who made a perfectly timed call to buy deeply depressed but high-quality corporate bonds at the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, called valuations on munis "increasingly compelling" with higher prospective after-tax returns than medium-grade corporate bonds or equities.

David Rosenberg, chief strategist at Gluskin Sheff, one of Canada's top wealth-management firms, adds that only single-B junk corporates provide the same after-tax yield as investment-grade munis. "I can't think of a security that is going to provide a U.S.-based investor a 7% annual return for the next decade with such little risk attached -- not equities, not corporates, not commodities. I still think this is the biggest opportunity out there in the investing world today and the most glaring price anomaly."

As the pace of fund liquidations has slowed to about $1 billion a week from $4 billion at the worst of the exodus in January, the muni market has begun to recover, with the iShares muni ETF up about 5% from its mid-January trough. In addition, issuers of municipal bonds deferred new offerings amid an inhospitable market.

Despite the undeniable value that munis represent, the dilemma remains for investors. As the news coverage of the budget battle raging in Madison, Wis., dramatically shows, state and municipal finances never have been under such stress.

But, as Clifford D. Corso, chief executive and chief investment officer of Cutwater Asset Management, points out, debt service makes up a small part of the expenses for states and localities -- in contrast to the sovereign debtors of Europe, for which interest and principal payments place a huge burden on their budgets.

The impact of the budget cuts being played out in state capitals and city halls across America will fall on public schools and the poor, as Howard Cure, director of municipal research at Evercore Wealth Management, a New York firm that manages separate accounts for high-net-worth individuals and families, ruefully observes.

Moreover, muni pros agree that states and localities have powerful incentives not to default in order to maintain their access to the capital markets. That is a direct contrast to the mortgage market, to whose parlous condition the municipal market has been compared, not entirely aptly. Borrowers whose mortgage balances are greater than their homes' values have engaged in what's euphemistically called "strategic defaults."

Yet the pressures on municipal finances are "episodic, not systemic," Cure adds. In other words, not every city is in the same dire straits as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania's capital, which averted default through by an advance from the state.

The greater risk in municipal bonds, most market professionals agree, is the same as for all fixed-income securities -- higher yields resulting from a more ebullient economy, rising inflation or both, which would be expected to lead to further losses. That has them taking some tacks that may appear counterintuitive.

Ken Woods, who heads Asset Preservation Advisors in Atlanta, which specializes in fixed-income management for high-net-worth individuals, is targeting a slightly longer duration for his clients' portfolios, which are concentrated in the intermediate-maturity range.

But for lengthening duration -- in a structure called a barbell -- he is concentrating on the very shortest maturities, under two years, and relatively longer ones out to eight-to-12 years. In the process, he's avoiding the middle of the range, which would be hurt the most by an increase in short-term interest rates by the Federal Reserve.

Corso of Cutwater Asset Management is taking the same barbell approach, concentrating on the short end and the long end of the market and avoiding intermediates. That is a strategy to deal with the extreme steepness of the muni yield curve -- the much greater yields paid on the longest maturities relative to shorter ones, which are anchored by the Fed's targeting of the overnight federal-funds rate near zero.

THIS ISN'T EUROPE

Headlines blare news of state and local budget woes, but many munis promise handsome returns. Especially appealing: bonds issued by agencies facing only modest retiree benefit costs.

Sample Portfolio

Maturity S&P Moody's Book Yield*

Texas A&M University 5/15/2012 AA+ Aaa 0.57%

San Antonio TX Elec & Gas 2/1/2014 AA Aa1 1.38

State of Pennsylvania GO 2/1/2014 AA Aa1 1.22

State of South Carolina GO 3/1/2016 AA+ Aaa 1.81

State of Utah GO 7/1/2016 AAA Aaa 1.85

Sutter Health - California 8/15/2016 AA- Aa3 3.37

Salt River Arizona Power Authority 1/1/2018 AA Aa1 2.53

State of Virginia GO 6/1/2019 AAA Aaa 2.54

Ascension Health - Michigan 11/15/2019 AA Aa1 3.87

State of Delaware GO 3/1/2020 AAA Aaa 2.75

State of Maryland GO 3/1/2021 AAA Aaa 2.90

Water/Sewer District of Southern California 3/1/2022 AAA Aaa 3.50

State of Texas GO 4/1/2023 AA+ Aaa 3.49

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 7/1/2023 AAA Aaa 3.42

State of North Carolina GO 5/1/2024 AAA Aaa 3.53

NYC Transitional Finance Authority 2/1/2025 AAA Aa1 4.17

Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority 7/1/2026 AAA Aa1 4.17

NYC Water/Sewer Authority 6/15/2028 AA+ Aa2 4.42

Charlotte NC Water/Sewer 7/1/2030 AAA Aaa 4.23.

Harvard University, Mass. 12/15/2031 AAA Aaa 4.27

Tallahassee, Fla. Health Facilities 12/1/2030 NA Baa1 6.43%

Halifax Hospital Medical Center, Fla. 6/1/20206 A- BBB+ 5.70

Northampton City, Pa., Hospital Authority 8/15/2024 BBB+ A3 5.58

Michigan Hosp. Fin. Auth. (Ford Health) 11/15/2039 A A1 6.28

Iowa Higher Ed. Ln. Auth. (Grinnell Col.) 12/1/2020 AAA Aaa 3.12

State of Washington GO 1/12/2020 AA+ Aa1 3.00

Illinois Fin Auth. (Swedish Covenant Hosp.) 8/15/2029 BBB+ A- 5.81

Denver City & Co Sch Dist. Colo 12/1/2021 AA- Aa2 3.30

*As of 03/02 Sources: Cutwater Asset Management & Asset Preservation Advisors

.

The muni yield curve's steepness parallels that of the Treasury market out to 10 years, but it becomes even more extreme for lengthier maturities. Two-year triple-A munis yield about the same as the two-year T-note -- as of March 3, around 0.72%. At 10 years, the muni yields 3.20% vs. 3.52% for the Treasury. But in 30 years, the muni yields 4.72% vs. 4.60% for the Treasury. For a taxpayer in what for now is the top federal tax bracket of 35%, the top-grade muni yields the equivalent of 7.26%, the same as better-grade corporate junk.

If, or when, the steepness of the muni yield curve corrects, with short- and intermediate-term yields likely moving higher, those on the short end of the barbell will be trading as near-cash equivalents and will be able to be redeployed at higher returns.

Historically, the long end typically doesn't move much in those circumstances, so the investor picks up significant yield with little price movement. In the less likely event the curve flattens from the long end, the lengthier maturities would rally.

Woods also is emphasizing medium-grade (triple-B and single-A) bonds to a greater extent since going down the quality scale provides greater-than-usual pickups in yield. But he does that for only some 15%-20% of portfolios, with 80%-85% in double-A or triple-A bonds instead of his usual 85%-90% in top grades.

Another emphasis is on longer-term, high-coupon callable bonds. For instance, instead of buying a bond maturing in eight or 10 years, Woods might buy a bond due in 18 years but callable in eight years with a high enough coupon to ensure it is called. These so-called kicker bonds provide a higher yield and lower volatility than comparable non-callable bonds. That's in part because they trade at a significant premium to par, and individuals not steeped in the arcane math of bonds are loath to pay above par.

Cure of Evercore emphasizes bonds outside the battlegrounds of budget deficits and future pension and retiree health-care benefits. While the news focus is on states and cities, there are thousands of bonds that are issued by various agencies. These securities have structures with clearly defined sources of money, either dedicated tax payments or revenues from the projects they finance.

In New York, Cure explains, personal-income-tax payments are dedicated to payment of bonds of the Housing Finance Agency, the Dormitory Authority and Thruway Authority. In Florida, there are bonds secured by state lottery revenues, which have to cover debt service three times.

Revenue bonds to finance essential services such as water and sewer systems also have the virtue of being relatively immune to vagaries in the economy, which affect income and sales-tax revenues. In addition, localities which depend on real-estate levies have been depressed by the drop in house prices.

Meanwhile, those authorities also have relatively few employees and lower future retirement liabilities than, say, school districts.

And just think of the satisfaction you'd get paying the toll on George Washington Bridge if you owned bonds of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates the Hudson River crossing.

.E-mail: editors@barrons.com

Copyright 2010 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. Distribution and use of this material are governed by our Subscriber Agreement and by copyright law. For non-personal use or to order multiple copies, please contact Dow Jones Reprints at 1-800-843-0008 or visit www.djreprints.com

Floating Rate Notes to Cope with Rising Interest Rates (Wall St Journal)

Floating-Rate Notes Resurface As Economy Grows Again

By Katy Burne of DOW JONES NEWSWIRES

NEW YORK (Dow Jones)--Corporate borrowers are switching up the composition of their debt sales, throwing more floating-rate notes into the mix to entice investors who believe interest rates may be about to rise sooner and faster than expected.

Nearly $26 billion, or 23%, of the investment-grade bonds marketed in the U.S. so far this year have had floating rates, according to data provider Dealogic, making it the busiest January for so-called floaters since 2007. That compares with $57.4 billion, or 7% of the supply, for all of 2010.

Bankers expect to see more floaters this year for two reasons: Issuers are suddenly comfortable selling them; and investors are eager to buy them to position their portfolios for a potential rise in rates.

"People have had the view for the last year, or year and a half, that short-term rates aren't going higher any time soon, and that is not an environment where you think you can make money on floating-rate debt," said Jim Merli, head of debt origination and syndicate at Nomura Holding Americas Inc.

"Now that is starting to change," Merli added, "because there is stronger economic data, and other central banks outside the U.S. are making noises about raising short-term rates."

Data over the last few months have been supportive of a more bullish outlook on the economy, with more job creation, a rising stock market, and strong corporate earnings over the past two weeks.

"While there are certainly headwinds like unemployment and weak wage gains, the data is far more balanced and the growth camp seems to have the scales tipping in its favor," said David Ader, head of government bond strategy at broker-dealer CRT Capital Group.

To be sure, floating-rate deals account for only a fraction of the market share they had in the middle of the last decade, and the volume outstanding has fallen by 40% since end of 2007 to $428.9 billion now. But issuers are warming up to them again.

Financial institutions tend to be the biggest issuers of floating-rate debt, to bring their funding in line with assets such as floating-rate loans. Financial firms, including insurers as well as banks, have accounted for 63% of the U.S. high-grade issuance in dollar volume so far this year, the highest percentage for any January since at least 1995, when Dealogic started keeping records.

About 57% of that total was from banks, although units of non-financials like brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV and energy giant Total SA have recently issued floaters, too.

AB In-Bev's strategy of pairing fixed- with floating-rate debt was "a function of the expected long-term recovery of the economy versus the short-term opportunity to benefit from historically low rates," said Scott Gray, director of global funding and financial markets at the company in New York.

Johnson Controls Inc. was in the market Tuesday with $350 million of three-year floating-rate notes as part of a $1.6 billion deal.

Heavy issuance by foreign banks has also contributed to the rise in these securities. They borrow in the U.S. because investor appetite is stronger here than in their domestic markets. January saw the largest volume of these so-called Yankee deals--dollar-denominated bonds sold by foreign firms in the U.S.--than any other month on record.

"Since the euro markets were less friendly to new issuance, floater deals that would normally have come as euro bonds were instead dollar issues," said Guy LeBas, chief fixed income strategist at Janney Capital Markets in Philadelphia.

Most of the floating-rate debt sold this year has been clustered around two- and three-year maturities, as was the case in 2009. Last year's issuance was more evenly spread between three-, five- and 10-year floaters, helping to stem the pace at which maturing debt exceeded new supply.

There is about $32 billion of floating-rate, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation-insured bonds under the government's Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program maturing this year, said LeBas, all of which needs to be refinanced--including $5 billion in the first quarter.

"Given that all the government-guaranteed debt from 2009 is maturing in 2011, banks will be able to issue short-term floaters beyond that maturity cliff," said Justin D'Ercole, head of Americas investment-grade syndicate at Barclays Capital. "As opposed to the last two years, when it would have had the effect of adding to their massive wall of maturities, it now fits into their debt-distribution profile."

LeBas said while there is marginally greater demand for floaters based on concerns about rising rates, investors are better off buying short-dated, fixed-rate debt. If rates rise and the income on the bond resets progressively higher, an investor would win out over time only if rates rise enough to offset the lower income in the early going.

"Rates would have to rise quite rapidly for it to make sense to accept such a low initial coupon," he said.

Last Thursday, ABN AMRO Bank N.V. sold $2 billion of fixed- and floating-rate bonds, with the $1 billion of floaters pricing at 1.77 percentage points over Libor, equivalent to a coupon of 2.07%, and the $1 billion of fixed-rate notes pricing with a coupon of 3%.

"Investors are using these floaters to shorten duration and express their view on the pace of future Fed tightening," said Michael Hyman, head of investment-grade credit at ING Investment Management, who participated in the ABN AMRO deal.

-By Katy Burne, Dow Jones Newswires; 212-416-3084; katy.burne@dowjones.com

By Katy Burne of DOW JONES NEWSWIRES

NEW YORK (Dow Jones)--Corporate borrowers are switching up the composition of their debt sales, throwing more floating-rate notes into the mix to entice investors who believe interest rates may be about to rise sooner and faster than expected.

Nearly $26 billion, or 23%, of the investment-grade bonds marketed in the U.S. so far this year have had floating rates, according to data provider Dealogic, making it the busiest January for so-called floaters since 2007. That compares with $57.4 billion, or 7% of the supply, for all of 2010.

Bankers expect to see more floaters this year for two reasons: Issuers are suddenly comfortable selling them; and investors are eager to buy them to position their portfolios for a potential rise in rates.

"People have had the view for the last year, or year and a half, that short-term rates aren't going higher any time soon, and that is not an environment where you think you can make money on floating-rate debt," said Jim Merli, head of debt origination and syndicate at Nomura Holding Americas Inc.

"Now that is starting to change," Merli added, "because there is stronger economic data, and other central banks outside the U.S. are making noises about raising short-term rates."

Data over the last few months have been supportive of a more bullish outlook on the economy, with more job creation, a rising stock market, and strong corporate earnings over the past two weeks.

"While there are certainly headwinds like unemployment and weak wage gains, the data is far more balanced and the growth camp seems to have the scales tipping in its favor," said David Ader, head of government bond strategy at broker-dealer CRT Capital Group.

To be sure, floating-rate deals account for only a fraction of the market share they had in the middle of the last decade, and the volume outstanding has fallen by 40% since end of 2007 to $428.9 billion now. But issuers are warming up to them again.

Financial institutions tend to be the biggest issuers of floating-rate debt, to bring their funding in line with assets such as floating-rate loans. Financial firms, including insurers as well as banks, have accounted for 63% of the U.S. high-grade issuance in dollar volume so far this year, the highest percentage for any January since at least 1995, when Dealogic started keeping records.

About 57% of that total was from banks, although units of non-financials like brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV and energy giant Total SA have recently issued floaters, too.

AB In-Bev's strategy of pairing fixed- with floating-rate debt was "a function of the expected long-term recovery of the economy versus the short-term opportunity to benefit from historically low rates," said Scott Gray, director of global funding and financial markets at the company in New York.

Johnson Controls Inc. was in the market Tuesday with $350 million of three-year floating-rate notes as part of a $1.6 billion deal.

Heavy issuance by foreign banks has also contributed to the rise in these securities. They borrow in the U.S. because investor appetite is stronger here than in their domestic markets. January saw the largest volume of these so-called Yankee deals--dollar-denominated bonds sold by foreign firms in the U.S.--than any other month on record.

"Since the euro markets were less friendly to new issuance, floater deals that would normally have come as euro bonds were instead dollar issues," said Guy LeBas, chief fixed income strategist at Janney Capital Markets in Philadelphia.

Most of the floating-rate debt sold this year has been clustered around two- and three-year maturities, as was the case in 2009. Last year's issuance was more evenly spread between three-, five- and 10-year floaters, helping to stem the pace at which maturing debt exceeded new supply.

There is about $32 billion of floating-rate, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation-insured bonds under the government's Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program maturing this year, said LeBas, all of which needs to be refinanced--including $5 billion in the first quarter.

"Given that all the government-guaranteed debt from 2009 is maturing in 2011, banks will be able to issue short-term floaters beyond that maturity cliff," said Justin D'Ercole, head of Americas investment-grade syndicate at Barclays Capital. "As opposed to the last two years, when it would have had the effect of adding to their massive wall of maturities, it now fits into their debt-distribution profile."

LeBas said while there is marginally greater demand for floaters based on concerns about rising rates, investors are better off buying short-dated, fixed-rate debt. If rates rise and the income on the bond resets progressively higher, an investor would win out over time only if rates rise enough to offset the lower income in the early going.

"Rates would have to rise quite rapidly for it to make sense to accept such a low initial coupon," he said.

Last Thursday, ABN AMRO Bank N.V. sold $2 billion of fixed- and floating-rate bonds, with the $1 billion of floaters pricing at 1.77 percentage points over Libor, equivalent to a coupon of 2.07%, and the $1 billion of fixed-rate notes pricing with a coupon of 3%.

"Investors are using these floaters to shorten duration and express their view on the pace of future Fed tightening," said Michael Hyman, head of investment-grade credit at ING Investment Management, who participated in the ABN AMRO deal.

-By Katy Burne, Dow Jones Newswires; 212-416-3084; katy.burne@dowjones.com

The Sleep at Night Portfolio: Make Your Own Pension (WSJ)

New ways to create a gold-plated pensionBY ELEANOR LAISE,

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal — 10/30/10

The financial crisis has given some investors a case of pension envy. In an era of volatile markets, the idea of steady, guaranteed payments for life holds obvious appeal.

The problem, of course, is that investors are less likely than ever to get that kind of deal from their employer. Companies tend to be freezing their pensions or closing them entirely, rather than beefing them up. About a third of today's Fortune 100 companies have frozen or closed a pension plan since 1998, according to consulting firm Towers Watson.

But that doesn't mean investors can't set up their own. New tools are emerging to help investors fashion portfolios that mimic the steady payments generated by the pension plans of yore.

The trick: to focus more on constructing a portfolio to cover future expenses—not just maximize returns—and to rethink old retirement-planning rules of thumb, such as a "safe" portfolio withdrawal rate of 4% annually.

Financial firms and advisers are catering to the demand for pension-like portfolios. New bond-based products can be tailored to produce income to pay living expenses for a period of, say, five or 10 years, leaving a significant chunk of the portfolio to invest in higher-growth assets with long-term potential. Some target-date mutual funds, meanwhile, are aiming to match their investments to the expenses investors face in retirement.

The new strategies often mean heftier helpings of bonds and inflation-fighting investments like real estate and commodities. While bigger bond holdings can mean lower returns, the approach also can give investors the confidence to stick with the more volatile stock investments in other parts of their portfolio, advisers say—reducing the chance they will sell shares at a market bottom.

When investors know that a few years' worth of basic expenses are covered by safe, high-quality bonds, "they can sit back and worry a whole heck of a lot less" about stocks' ups and downs, says Joe Chrisman, director at wealth-management firm Lourd Capital Management, which uses a pension-style approach with clients.

The most painful part of the process may be simply saving more. Since the financial crisis, "there's been a much greater recognition that the markets are not going to rescue everyone," says Timothy Noonan, managing director at Russell Investments. Building a secure retirement "is not a function of going and finding higher returns."

The pension approach seems to work: Over the long term, defined-benefit pension plans have outperformed 401(k) plans by roughly 1 percentage point annually, according to Towers Watson.

Small investors can't—and shouldn't—invest exactly like pension plans, though. For a pension plan acting on behalf of many beneficiaries, with people entering and retiring each year, the age of an individual worker makes little difference. But a person investing on his own must tone down portfolio risk—and generally accept lower returns—as he approaches retirement.

Pension plans also can buy into some investments that most small investors can't access, such as hedge funds and private equity, and get better deals on fees.

That isn't to say pension plans have some magic formula. Many suffered big losses in 2008, for example, though overall they held up better than 401(k)s, according to Towers Watson.

Neither type of retirement plan provides the perfect answer, says Zvi Bodie, a finance and economics professor at Boston University School of Management. "We need to combine the best of both."

Annuities may seem the simplest solution for investors seeking a steady income stream. One approach: Buy an immediate annuity that provides for basic expenses, leaving other parts of the portfolio to cover nonessentials. A number of firms now are working to marry funds with annuities within 401(k) plans.

Still, many advisers suggest investors first consider the greater flexibility, and often lower costs, that can come with a do-it-yourself approach.

A homemade pension plan starts by acknowledging that people, like companies, have a balance sheet with both assets and liabilities, advisers say. The liabilities include the money you will spend on food, shelter, travel and other expenses. Yet advisers and money managers traditionally have focused mostly on the assets, trying to maximize investment returns for a given level of risk.

Pensions, by contrast, are more likely to employ liability-driven investing, choosing particular investments to match their future expenses. Investors can do this, too—by buying long-term bonds, for example, to match payments to be made decades from now.New tools can help people size up future expenses. At goalgami.com, a free calculator launched earlier this year by financial-planning technology firm Advisor Software Inc., people can enter information on their income, assets, debt and long-term goals like real-estate purchases. Taking a lifetime view of the "household balance sheet," rather than a single snapshot, the tool analyzes whether future sources of cash will pay the bills and cover other retirement costs.

Most people want to maintain their standard of living in retirement. So if you have just retired and live comfortably on $100,000 a year, you want that income to keep up with inflation as long as you live, says Tom Idzorek, chief investment officer at Morningstar Inc.'s Ibbotson Associates.

A "laddered" portfolio of Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, can help. Investors who buy TIPS that mature in each year of retirement ensure a steady income stream that rises with inflation and matches spending, Mr. Idzorek says.

Ibbotson in recent years has been designing target-date fund strategies with retirement liabilities in mind. It has built two sample portfolios—one using traditional asset allocation and one with a liability-focused approach—that have roughly the same allocations to stocks and bonds. But the liability-focused portfolio allocates roughly 28% to assets that can act as inflation hedges, including commodities and real estate, versus about 16% in the traditional portfolio.

Since people are likely to spend their retirement money in U.S. dollars, they also can more closely match their assets with their liabilities by investing more in U.S. stocks and bonds as they approach retirement, Mr. Idzorek says. In the sample portfolios, the liability-focused approach devotes only about 8% to non-U.S. holdings, versus about 18% in the traditional portfolio.

The liability-focused portfolio's expected return, 5.9%, is only slightly less than the 6.4% expected in the traditional portfolio, according to Ibbotson.

Of course, given the recent bond rally, it can be pricey to match many years' worth of retirement expenses with TIPS and other bond investments. Asset Dedication LLC, a Mill Valley, Calif., money-management firm, aims to address that by building custom bond portfolios to produce precisely the income to cover client expenses for a given number of years, leaving plenty to invest in higher-growth assets.

The firm's Defined Income product, launched this year, invests in certificates of deposit, TIPS and other high-quality bonds and holds them to maturity. Bulking up on fixed-income might seem counterintuitive right now. But by holding bonds to maturity and then rolling them over, the strategy can capitalize on higher yields later.

If a client wants to spend $50,000 in each of the next five years but also wants to buy a vacation home in year three, the account can help plan for that, says Mr. Chrisman of Lourd Capital, which uses the Asset Dedication program and other liability-driven strategies with clients.

Mickey Patrick, 57 years old, says his do-it-yourself pension allows him to stop worrying about short-term stock-market swings. Mr. Patrick, a technology manager in Houston, earlier this year started investing most of his individual retirement account in TIPS, CDs and other high-quality bond holdings. Though several financial advisers had told him to keep most of the money in stocks, Mr. Patrick determined that the account needed to cover only about one-fourth of his retirement spending, since a pension and Social Security would provide the rest—and therefore he didn't need to take that much risk.

"They said I was crazy," Mr. Patrick says. But while he used to check market moves daily, now "I don't worry at all about it," he says.

People who are focused on matching investment assets with retirement "liabilities" challenge some conventional retirement-planning wisdom. One rule of thumb says investors should have a stock allocation equal to 100 minus their age. (A 40-year-old, for example, would keep 60% in stocks.) But Boston University's Mr. Bodie says risk-averse investors, even younger ones, might want to put most of their money in safer assets.

Bob Kirchner, 63, a retired economist in Fort Washington, Md., has found that a liability-matching strategy reverses the traditional planning process. Instead of first deciding to put, say, 50% in stocks, he says, it's "let's get all this safe stuff lined up first," leaving stock decisions for later. He now has more than half of his portfolio in TIPS.

Liability-driven investing also involves rethinking the "safe" portfolio-withdrawal rate. Many advisers say retirees can withdraw 4% of their initial retirement balance a year, adjusting annually for inflation. But while the 4% spending rule is rigid, the investments tend not to be. Someone might automatically spend a preset amount, disregarding the fact that his portfolio has gained or lost, say, 30% over the past year. With the 4% rule, "there's a chance you'll wind up with nothing, and there's a bigger chance you'll leave quite a bit," says William Sharpe, a professor of finance, emeritus, at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

A bill introduced in Congress last year would require 401(k)s to show participants a projected monthly retirement income based on their current account balance, instead of just a simple lump sum. Russell Investments is developing tools to help financial advisers look at similar metrics for clients' portfolios, says Russell's Mr. Noonan.

If investors can look at their progress in terms of their personal goals rather than market events, Mr. Noonan says, "it's easier for them to remain invested when the market is doing scary gyrating things."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright © 2010 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserv

The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal — 10/30/10

The financial crisis has given some investors a case of pension envy. In an era of volatile markets, the idea of steady, guaranteed payments for life holds obvious appeal.

The problem, of course, is that investors are less likely than ever to get that kind of deal from their employer. Companies tend to be freezing their pensions or closing them entirely, rather than beefing them up. About a third of today's Fortune 100 companies have frozen or closed a pension plan since 1998, according to consulting firm Towers Watson.

But that doesn't mean investors can't set up their own. New tools are emerging to help investors fashion portfolios that mimic the steady payments generated by the pension plans of yore.

The trick: to focus more on constructing a portfolio to cover future expenses—not just maximize returns—and to rethink old retirement-planning rules of thumb, such as a "safe" portfolio withdrawal rate of 4% annually.

Financial firms and advisers are catering to the demand for pension-like portfolios. New bond-based products can be tailored to produce income to pay living expenses for a period of, say, five or 10 years, leaving a significant chunk of the portfolio to invest in higher-growth assets with long-term potential. Some target-date mutual funds, meanwhile, are aiming to match their investments to the expenses investors face in retirement.

The new strategies often mean heftier helpings of bonds and inflation-fighting investments like real estate and commodities. While bigger bond holdings can mean lower returns, the approach also can give investors the confidence to stick with the more volatile stock investments in other parts of their portfolio, advisers say—reducing the chance they will sell shares at a market bottom.

When investors know that a few years' worth of basic expenses are covered by safe, high-quality bonds, "they can sit back and worry a whole heck of a lot less" about stocks' ups and downs, says Joe Chrisman, director at wealth-management firm Lourd Capital Management, which uses a pension-style approach with clients.

The most painful part of the process may be simply saving more. Since the financial crisis, "there's been a much greater recognition that the markets are not going to rescue everyone," says Timothy Noonan, managing director at Russell Investments. Building a secure retirement "is not a function of going and finding higher returns."

The pension approach seems to work: Over the long term, defined-benefit pension plans have outperformed 401(k) plans by roughly 1 percentage point annually, according to Towers Watson.

Small investors can't—and shouldn't—invest exactly like pension plans, though. For a pension plan acting on behalf of many beneficiaries, with people entering and retiring each year, the age of an individual worker makes little difference. But a person investing on his own must tone down portfolio risk—and generally accept lower returns—as he approaches retirement.

Pension plans also can buy into some investments that most small investors can't access, such as hedge funds and private equity, and get better deals on fees.

That isn't to say pension plans have some magic formula. Many suffered big losses in 2008, for example, though overall they held up better than 401(k)s, according to Towers Watson.

Neither type of retirement plan provides the perfect answer, says Zvi Bodie, a finance and economics professor at Boston University School of Management. "We need to combine the best of both."

Annuities may seem the simplest solution for investors seeking a steady income stream. One approach: Buy an immediate annuity that provides for basic expenses, leaving other parts of the portfolio to cover nonessentials. A number of firms now are working to marry funds with annuities within 401(k) plans.

Still, many advisers suggest investors first consider the greater flexibility, and often lower costs, that can come with a do-it-yourself approach.

A homemade pension plan starts by acknowledging that people, like companies, have a balance sheet with both assets and liabilities, advisers say. The liabilities include the money you will spend on food, shelter, travel and other expenses. Yet advisers and money managers traditionally have focused mostly on the assets, trying to maximize investment returns for a given level of risk.

Pensions, by contrast, are more likely to employ liability-driven investing, choosing particular investments to match their future expenses. Investors can do this, too—by buying long-term bonds, for example, to match payments to be made decades from now.New tools can help people size up future expenses. At goalgami.com, a free calculator launched earlier this year by financial-planning technology firm Advisor Software Inc., people can enter information on their income, assets, debt and long-term goals like real-estate purchases. Taking a lifetime view of the "household balance sheet," rather than a single snapshot, the tool analyzes whether future sources of cash will pay the bills and cover other retirement costs.

Most people want to maintain their standard of living in retirement. So if you have just retired and live comfortably on $100,000 a year, you want that income to keep up with inflation as long as you live, says Tom Idzorek, chief investment officer at Morningstar Inc.'s Ibbotson Associates.

A "laddered" portfolio of Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, can help. Investors who buy TIPS that mature in each year of retirement ensure a steady income stream that rises with inflation and matches spending, Mr. Idzorek says.

Ibbotson in recent years has been designing target-date fund strategies with retirement liabilities in mind. It has built two sample portfolios—one using traditional asset allocation and one with a liability-focused approach—that have roughly the same allocations to stocks and bonds. But the liability-focused portfolio allocates roughly 28% to assets that can act as inflation hedges, including commodities and real estate, versus about 16% in the traditional portfolio.

Since people are likely to spend their retirement money in U.S. dollars, they also can more closely match their assets with their liabilities by investing more in U.S. stocks and bonds as they approach retirement, Mr. Idzorek says. In the sample portfolios, the liability-focused approach devotes only about 8% to non-U.S. holdings, versus about 18% in the traditional portfolio.

The liability-focused portfolio's expected return, 5.9%, is only slightly less than the 6.4% expected in the traditional portfolio, according to Ibbotson.

Of course, given the recent bond rally, it can be pricey to match many years' worth of retirement expenses with TIPS and other bond investments. Asset Dedication LLC, a Mill Valley, Calif., money-management firm, aims to address that by building custom bond portfolios to produce precisely the income to cover client expenses for a given number of years, leaving plenty to invest in higher-growth assets.

The firm's Defined Income product, launched this year, invests in certificates of deposit, TIPS and other high-quality bonds and holds them to maturity. Bulking up on fixed-income might seem counterintuitive right now. But by holding bonds to maturity and then rolling them over, the strategy can capitalize on higher yields later.

If a client wants to spend $50,000 in each of the next five years but also wants to buy a vacation home in year three, the account can help plan for that, says Mr. Chrisman of Lourd Capital, which uses the Asset Dedication program and other liability-driven strategies with clients.

Mickey Patrick, 57 years old, says his do-it-yourself pension allows him to stop worrying about short-term stock-market swings. Mr. Patrick, a technology manager in Houston, earlier this year started investing most of his individual retirement account in TIPS, CDs and other high-quality bond holdings. Though several financial advisers had told him to keep most of the money in stocks, Mr. Patrick determined that the account needed to cover only about one-fourth of his retirement spending, since a pension and Social Security would provide the rest—and therefore he didn't need to take that much risk.

"They said I was crazy," Mr. Patrick says. But while he used to check market moves daily, now "I don't worry at all about it," he says.

People who are focused on matching investment assets with retirement "liabilities" challenge some conventional retirement-planning wisdom. One rule of thumb says investors should have a stock allocation equal to 100 minus their age. (A 40-year-old, for example, would keep 60% in stocks.) But Boston University's Mr. Bodie says risk-averse investors, even younger ones, might want to put most of their money in safer assets.

Bob Kirchner, 63, a retired economist in Fort Washington, Md., has found that a liability-matching strategy reverses the traditional planning process. Instead of first deciding to put, say, 50% in stocks, he says, it's "let's get all this safe stuff lined up first," leaving stock decisions for later. He now has more than half of his portfolio in TIPS.

Liability-driven investing also involves rethinking the "safe" portfolio-withdrawal rate. Many advisers say retirees can withdraw 4% of their initial retirement balance a year, adjusting annually for inflation. But while the 4% spending rule is rigid, the investments tend not to be. Someone might automatically spend a preset amount, disregarding the fact that his portfolio has gained or lost, say, 30% over the past year. With the 4% rule, "there's a chance you'll wind up with nothing, and there's a bigger chance you'll leave quite a bit," says William Sharpe, a professor of finance, emeritus, at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

A bill introduced in Congress last year would require 401(k)s to show participants a projected monthly retirement income based on their current account balance, instead of just a simple lump sum. Russell Investments is developing tools to help financial advisers look at similar metrics for clients' portfolios, says Russell's Mr. Noonan.

If investors can look at their progress in terms of their personal goals rather than market events, Mr. Noonan says, "it's easier for them to remain invested when the market is doing scary gyrating things."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright © 2010 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserv

Obama and Annuities (New York TImes)

January 30, 2010

Your Money

The Unloved Annuity Gets a Hug From Obama

By RON LIEBER

Annuities: The official retirement vehicle of the Obama administration.

As slogans go, it’s hardly “Keep Hope Alive,” or even “Change We Can Believe In.”

But there were annuities, in a report from the administration’s Middle Class Task Force that came out this week. They are among the tools the administration is promoting as it tries to give Americans a better shot at a more secure retirement.At its simplest, which is how the White House seems to want to keep it, an annuity is something you buy with a large pile of cash in exchange for a monthly check for the rest of your life.