What You Will Find Here

- OJOS11

- Articles and news of general interest about investing, saving, personal finance, retirement, insurance, saving on taxes, college funding, financial literacy, estate planning, consumer education, long term care, financial services, help for seniors and business owners.

READING LIST

-

▼

2011

(56)

-

▼

September

(9)

- Estate Planning Blunders of the Stars (Investment ...

- emerging markets: CIVETS and BRICS (wsj)

- Combat Inflation with Floating Rate Securities (F...

- Potential for Countrywide Default (Bloomberg)

- Top 10 Investment Scams (NASAA.org)

- The GAO Report on Immediate Annuities

- The Best and the Worst States for Muni Bonds (Barr...

- What College Degrees Will Get You A GOOD Job? What...

- Nine Most Common IRA Mistakes (the Dolans)

-

▼

September

(9)

Blog List

-

-

Trump to Roll Back Some Steel and Aluminum Tariffs Due to Inflation - The Financial Times discusses tariff rollbacks.

-

Past crypto winters show bitcoin could keep tumbling to $31,000, research firm says - In past bitcoin winters, the crypto has dropped an average 84%, according to an analysis from Ned Davis Research.

-

More Epstein Fallout for Goldman Sachs, DP World and Beyond - The Wall Street giant’s top lawyer, whose ties to Jeffrey Epstein had raised questions at the firm, has resigned. Other corporate leaders are also facing b...

-

Everybody Else Is Reading This - Snowflakes That Stay On My Nose And Eyelashes Above The Law Trump’s New Birth Control […]

-

Maximizing Employer Stock Options - Oct 29 – On this edition of Lifetime Income, Paul Horn and Chris Preitauer discuss the benefits of employee stock options and how to best benefit from th...

-

Wayfair Needs to Prove This Isn't as Good as It Gets - Earnings were encouraging, but questions remain about the online retailer's long-term viability.

-

Hannity Promises To Expose CNN & NBC News In "EpicFail" - *"Tick tock."* In a mysterious tweet yesterday evening to his *3.19 million followers,* Fox News' Sean Hannity offered a preview of what is to come from ...

-

Don’t Forget These Important Retirement Deadlines - *Now that fall is in full swing, be sure to mark your calendar for steps that can help boost your tax-advantage retirement savings.*

The Best and the Worst States for Muni Bonds (Barrons)

Barron's Cover | MONDAY, AUGUST 29, 2011

Good, Bad and Ugly

By JONATHAN R. LAING There's hope for states that accept structural change, but pain for those that won't. Are you listening, Illinois and California?

For most states, fiscal 2012 is shaping up as a brutal year. They've already had to close a collective gap of more than $100 billion between their projected revenues and previously budgeted expenses, mostly due to anemic sales taxes and personal and corporate-income levies. And all this comes after three years of large budget shortfalls, during which most of the low-hanging fruit in expenses had been plucked and rainy-day funds and other reserves had been plundered.

Likewise, just about all of the $165 billion in federal stimulus money that had helped to close state budget gaps since the 2008-09 financial crisis has been spent. Thus, the cuts for fiscal 2012, which for most states began last month, promise to be particularly painful, leading to employee layoffs and reduced human-services spending on programs such as Medicaid.

Education will bear the brunt, as states are forced to trim their funding to public universities and K-through-12 school districts. The latter, particularly in low-income areas, will especially suffer from the lagged effect of the housing bust on a falling property-tax take.

Yet there's hope amid the gloom for many of the states, and for the $1.5 trillion state municipal-bond market. Tax revenue has begun to rise again, after falling cataclysmically for five straight quarters during the Great Recession.

In fact, state-tax revenue in fiscal 2011's first quarter was up 9.3%, on average, over the year-earlier figure, reports the respected Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government at the State University of New York at Albany. This was the fifth straight quarterly improvement. To be sure, the revenue picture could darken if the U.S. economy double-dips. (The numbers in each category in the tables accompanying this article generally are based on the most recent and comprehensive data available, and so their dates don't all coincide. However, they do paint a good picture of each state's relative position against the others.)

And since the 2010 elections, new governors, mostly Republican, have come to the fore, unbeholden to the public-employee unions that have used political muscle to win cushy contracts and fat retiree pension and health benefits. The roster of new-breed, social-Darwinist figures includes the likes of Scott Walker of Wisconsin, John Kasich of Ohio, Rick Scott of Florida and Chris Christie of New Jersey, all following the successful path of two-term Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels. Even prominent Democrat and New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, scion of a family steeped in Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, has pushed state unions to accept contracts with a three-year wage freeze and five unpaid furlough days in the current fiscal year.

The governors want the unions to contribute more to their pension funds and health plans to ensure the systems' soundness. Controversially, Walker and Kasich even have tried to convince the unions to surrender or reduce their collective-bargaining rights. Moreover, many states are creating new tiers of public employees provided with much less munificent pension and health-care plans. Retirement ages are being boosted, automatic cost-of-living adjustments to pensions are being eliminated, pension vesting periods are being increased and shenanigans like income-spiking at the end of careers to fatten benefits are being banned. Such moves will do much to ameliorate a long-term pension and retiree health-benefit funding gap that The Pew Center on the States puts at $1.26 trillion.

At the same time, some states, including New York, are trying to cap and slow property-tax hikes. And while such governors as Walker, Christie and Scott are putting the axe to spending, they're also cutting taxes on corporations and the wealthy, with the aim of boosting employment and investment. Wisconsin even scaled back its earned-income tax credit for 152,000 working families ($518 for a family of five), to partially defray the cost of tax cuts for big earners. Trickle-up economics is in vogue in these states.

The process has been messy and, sometimes, noisy; witness the union demonstrations at the capitol building in Madison, Wis., in February. Yet the municipal-bond market has rallied sharply since late last year, when banking seer Meredith Whitney set off a panic by predicting that there would be as many as 100 major muni-bond defaults in calendar year 2011, totaling $100 billion or more, because of state and local financial problems. Through Aug. 12, a recent Bank of America Merrill Lynch report notes that defaults have been modest this year, at $757.8 million, or just 0.026% of total outstanding municipal debt. And most of the troubled issuers have been small ones that depend on revenue from special-assessment districts, housing developments and hospital complexes, not general tax revenues.

To Howard Cure, director of municipal research at Evercore Wealth Management in New York, it's "inconceivable" that any state will default on its general-obligation debt. According to Cure, the only risk that investors run in state debt, beyond the risk that could arise if interest rates jump, would come from credit downgrades or a change in market perceptions of a state's financial prospects, which could quickly push down prices of existing state bonds.

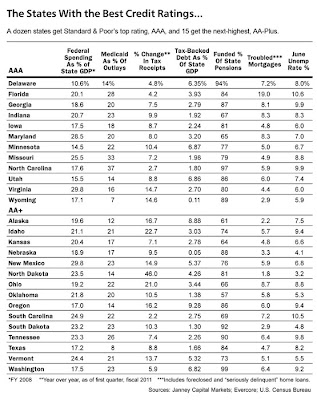

To help investors, the tables Barron's has compiled show how all 50 states rank, based on seven key financial and economic variables. The data were compiled by Janney Capital Markets and Evercore. The states are sorted by their Standard &Poor's credit ratings to make comparisons easier.

Our first statistic shows the amount of federal spending each state receives as a percentage of the state's gross domestic product. The source can be: defense or nondefense work; procurement contracts; grants; and salaries and wages paid to state residents by Uncle Sam. This reading is particularly timely, in that federal outlays face cuts for years to come, due to growing budget-deficit stringency.

Here, a couple of triple-A names -- Virginia and Maryland -- stick out. Federal spending accounts for 29.8% of Virginia's economy and 28.5% of Maryland's, far above the 19.7% that's the average in the U.S. Just think of all the federal employees who live in Arlington or Bethesda but work in Washington, or of the hordes who labor in the vast office parks outside the Beltway, filled with government consultants and federal contractors. The credit-rating firm Moody's has both states on "negative outlook" in the wake of the national-debt anxiety.

Medicaid as a percentage of total state spending is another key indicator. Nationally, the program, which provides health care for the poor, accounts for 21% of all state spending -- and will loom much larger if the Obama health reforms are upheld by the courts and fold in millions of currently uninsured into Medicaid, for which the federal government picks up about half the tab. Already, however, like Pac-Man, the program has ferociously eaten away at state financial resources due tomedical-cost inflation and rising enrollment.

Here, comparisons are difficult, because some states, like California (22%) and Illinois (33%), offer a far more extensive range of services than, say, Texas (8%). The Lone Star state also benefits because some members of its large Hispanic population are reluctant to sign up for government programs due to citizenship issues.

States with large urban underclasses also tend to have higher Medicaid rolls. That has swelled their spending -- New York's by 28%, Pennsylvania's by 28% and, of course, Illinois' (above). Not surprisingly, to curb the rise in Medicaid costs, states like New York are considering moving away from their current fee-for-service payment systems to managed care.

Tax-collection growth is where the rubber meets the road for most states. Many of the stars in this respect are benefiting from rising prices for oil, food and minerals. North Dakota had a 46% jump in first-quarter fiscal 2011 collections, boosted by exploitation of the gas- and oil-rich Bakken shale shelf. Alaska, with its tax take up by 16.7%, likewise benefited from higher oil prices.

Even some Rust Belt states -- Michigan (up 20.9%) and Ohio (up 22%) were helped, in part, by improved manufacturing. But, tax increases were the biggest factor in the improved revenue numbers. Illinois (up 13.7%) raised personal income and corporate levies at the beginning of calendar-year 2011. California, on the other hand, saw a package of emergency tax increases expire at the end of fiscal 2010, and thus realized a paltry 5.7% rise in tax receipts in fiscal 2011's first quarter, and there's little reason to believe that the situation has improved. So the no-longer-so-Golden State could face additional budget shortfalls in the current fiscal year.

Overall, however, tax-supported state debt as a percentage of state gross national product has hardly reached alarming levels. Even states like Connecticut and Hawaii, whose debt exceeds 10% of their gross domestic products, aren't basket cases. Both centralize more functions that local governments do elsewhere, so the figures are a bit deceiving.

The same doesn't hold true for the chronic underfunding problems of state public-employee pension plans. The public-employee pension funding gap accounts for around $660 billion of the aforementioned $1.26 trillion retiree-benefits shortfall tabulated by Pew. And unlike retiree health care, pension benefits are harder to fix.

Particularly shaky are states like Illinois, with only 51% of its pension obligations funded, and California, with 81%. Their dysfunctional state governments, allied with public-employee unions, are seemingly incapable of making needed reforms. Several times in recent years, Illinois has floated bond issues to make its pension contributions, only to find that it paid more in interest on them than it made on its investments.

The last two factors in our tables are the percentage of mortgages in foreclosure or seriously delinquent -- meaning 90 days in arrears -- as of fiscal 2011's first quarter, and the state's unemployment rate.

Florida, Nevada, Arizona and California still have big mortgage problems, stemming from the faux housing boom of the George W. Bush years. That encouraged local governments to wildly expand, using soaring property-tax revenue, and individuals to spend more, by taking out home-equity loans. When the boom ended, the spending did, too, and joblessness soared. Based on June numbers, the states with the worst jobless rates were Florida (10.6%), and Michigan and South Carolina (both 10.5%).

In sum, our tables should provide some clues for muni-bond investors puzzling out where to invest. But the most important factor isn't listed -- a state's willingness to embrace structural change. In that regard, Illinois and California bring up the rear.

.E-mail: editors@barrons.com

Copyright 2011 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved